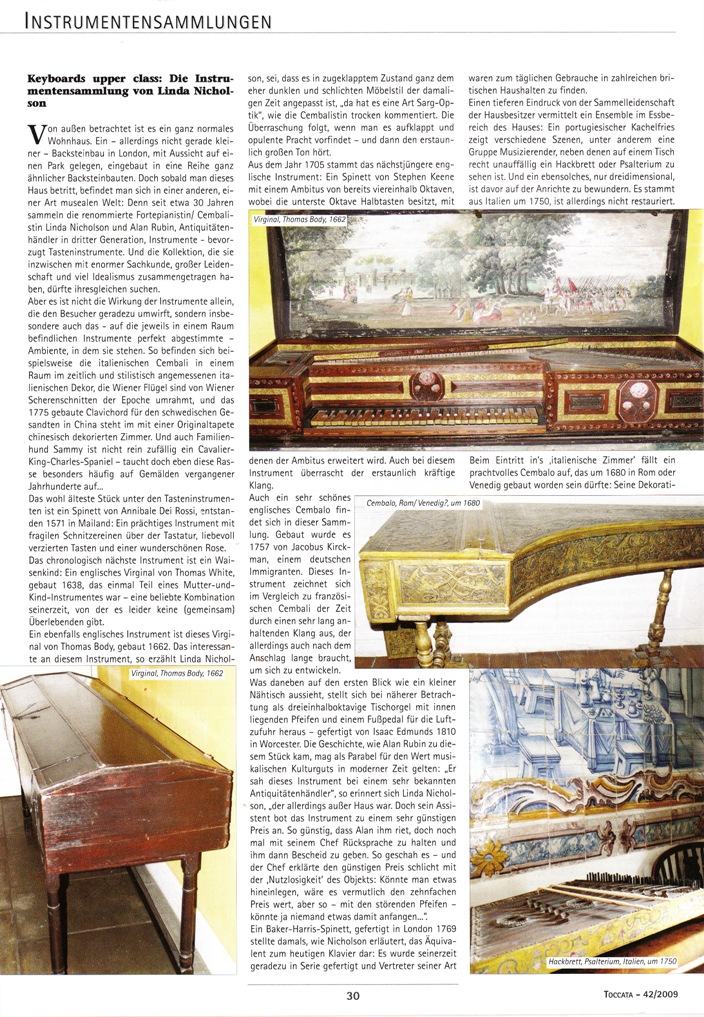

Toccata July/August 2009 Keyboards upper class: the collection of Linda Nicholson (English translation) Viewed from the outside, it seems to be quite a normal home. A brick building in London– albeit not exactly small, overlooking a park, one of a row of similar brick buildings. However as soon as one enters this house, one finds oneself in another, highly keyboard orientated, world: for Linda Nicholson, the well-known fortepianist, and her husband, a third-generation antique dealer, have been collecting instruments for about thirty years, predominantly keyboard instruments. And this collection–clavichords, harpsichords, spinets, virginals, fortepianos, square pianos, organs and other items on which music can be produced in some way– was put together in the course of three decades with enormous knowledge, great passion and much idealism. However it is not just the instruments that strike the visitor, but altogether the ambience in which they stand: the fact that in each respective room the instruments are most precisely matched historically and stylistically. And that conveys an idea of the passion with which Nicholson and Rubin cultivate their interest. So, for example, the Italian harpsichords are in a room with an Italian decor of the appropriate style and date, the Viennese pianos are surrounded by Viennese silhouettes of the period, and the 18th century clavichord possibly made for the Swedish envoy to China stands in a room decorated in the Chinese style. And it is not by chance that the family's dog, Sammy, is a Cavalier King Charles spaniel– this breed often appears in paintings of previous centuries and even on the lid of a clavichord.... The oldest of the keyboard instruments is a spinet by Annibale dei Rossi, made in 1571 in Milan: a marvellous instrument with fragile carvings above the keyboard, lovely decorated keys and a beautiful rose. Chronogically the next instrument is an orphan: an English virginals by Thomas White, built in 1638, which was part of a mother-and-child instrument– a popular combination at the time, but of which there are sadly no complete examples remaining. Another English instrument is this virginals by Thomas Body, dated 1662. Linda Nicholson explains that the interesting feature of this instrument is that in its closed form it conforms to the dark and sober style of furniture of that period: " it looks rather like a coffin", as the harpsichordist drily comments. What is surprising, is the opulent splendour one finds on opening it– and then hearing the unbelievably full sound. There is also a very beautiful English harpsichord in this collection. It was built in 1757 by Jacob Kirckman, a German immigrant. In contrast to French harpsichords of this period the sound of this instrument lasts for a very long time, and needs a while to develop after the attack. What at first glance appears to be a side table proves on closer inspection to be a three-and-a-half octave table organ with pipes that lie inside and a foot pedal to pump the air– made by Isaac Edmunds in Worcester in 1810. The story of how Linda's husband acquired this piece might serve as a parable about the value of musical culture in modern times. "He saw this instrument at a well-known antique dealer ", remembers Linda Nicholson, "who was out of the shop at the time. However his assistant offered the instrument at a very favourable price. So favourable, that he asked him to check with his boss that it was correct and then let him know. The boss explained the favourable price quite simply with the 'uselessness' of the object. If one could put something in it, it might be worth ten times as much, but with the annoying pipes inside, no-one could do anything with it.... A Baker Harris spinet, made in London in 1769, was the equivalent of the upright piano today. In its day they were made in quantities and examples of this type were to be found in numerous British households. An ensemble in the eating portion of the house gives a deeper impression of the house-owner's passion for collecting. A Portuguese tile panel shows various scenes, amongst others a group of musicians near to whom lies a dulcimer or psaltery. And another like it, only three-dimensional, lies before it on the dresser to be admired. From Italy, circa 1750, it is unrestored. On entering the 'Italian' room a splendid harpsichord stands out, that was made in Rome or Venice in about 1680. Its decoration consists of intertwined ornaments in gold, silver (which has since tarnished) and blue, and it produces the typical bright and penetrating Italian sound with its iron strings. Its restoration shed light on an interesting feature of Italian harpsichord building at this time: burnt wood shavings were found inside the case. These, still glowing or burning, kept the glue hot until the soundboard was fixed. Once it was set the ashes went out due to the lack of oxygen. A small three-octave Italian ottavina, richly decorated with carvings, completes the arcadian part of the collection. It is a light, portable table instrument from about 1580, with a small ornamented glass plaque above the keyboard that has miraculously survived. It is not yet restored. The clavichord that has already been mentioned, possibly made for the Swedish envoy to China by Per Lundborg in 1775, is decorated in the Chinese style– as, some 200 years later, was the room in which it stands. The wallpaper with Chinese scenes dates from the late 18th or early 19th century. The organ that greets the visitor in the entrance hall of Linda Nicholson's home is from circa 1775. Made in Holland, probably by a German builder, it is richly decorated with figures and gilding. With its twelve stops it is endowed with a really opulent sound for such a small instrument. A clavichord made by Johann Adolf Haas in 1767 has a particularly beautiful lid painting showing pastoral scenes, and rejoices in keys richly inlaid with ivory, mother-of-pearl and tortoiseshell. The square piano made by the German émigré, Johannes Zumpe, in 1773 has a particular historical significance. It was on just such an instrument that J.C.Bach first performed a piano concerto in public, in 1768. Rubin found a two-manual French harpsichord of 1757 in the wine cellar of a French lacquer restorer, and rescued it from the damp room. It has two 8' stops and one 4', plus a lute stop, and was made by Jean Goermans. The beautiful rosette of this instrument is aesthetically especially pleasing. The collection continues with another French harpsichord by Pierre Donzelague, Lyon 1711, an instrument with the same disposition as the Goermans, which has been much copied. An unusual feature is that the lid is not painted directly on the wood, but has a canvas stretched on it. It seems likely that a further French instrument with lavish gold decoration and fine painting must have been made for an important palace or nobleman's house. It was originally built by Joannes Couchet in circa 1620, but was later enlarged by Blanchet in the 18th century, as was customary at the time. The French atmosphere of the room is further enhanced by a French 18th century harp and a hurdy-gurdy of circa1740 by Pierre Louvet. The upright Irish piano that one discovers in another room reminds one of a fairground at first glance. One would not associate the many colours and the material with which it is ornamented with the date 1800, when it was built by William Southwell. There is another, very innovative, instrument by the same maker, that is actually a half-round piano with an ingenious method of closing–from the lid to the folding music stand. A barrel organ plays "Rule Britannia": this is surrounded by a folding quartet stand for four singers or instrumentalists, and, to complete the English ensemble, a piano with English action by the famous maker John Broadwood (1808) stands nearby. Its sound is fuller and louder, but with less attack, than the Viennese pianos of this period– an idea that so fascinated Joseph Haydn that he brought the idea back with him to Vienna. The guest now enters the German, or Austrian, realm with a glass harmonica from the 1790's. A footpedal turns the overlapping glass dishes of the instrument: a singing sound is produced by dipping the fingers in water and touching the rims. Very thick glass dishes, moreover, so that this instrument does not differ in weight very much from a full-scale piano! The collection also includes a German 'Tangentenflügel' of the 1790's, made by Schmahl. Johann Rey and Sons produced a square piano in Amsterdam in 1815/20 that also has space for music, paper, and writing materials in an extra drawer. The Viennese room offers a completely different, and no less impressive, musical and aesthetic experience. Six Viennese pianos and various small instruments are crammed in, surrounded by silhouettes of the most famous people in Vienna at the end of the 18th century. A pottery stove in the form of an organ ornaments the wall; at the other end of the room stands a clock containing a real flute and piano, that plays duets with itself when wound up. This richly artistic item of furniture was made in Germany in about 1780. Another instrument, that even on second glance does not betray that it is anything other than a simple secretaire, reveals on closer (much closer) inspection, that it contains a barrel organ. This instrument, made in Vienna around 1820, is prettily decorated and really very easy to work with its pipes concealed inside. The earliest fortepiano in this room was made by Johann Schantz in about 1797.This five-octave (and two notes) piano sounds considerably harder with its Viennese mechanism than its Broadwood colleague nearby. A five octave (and one note) instrument by Anton Walter is from the same year, 1797, and is somewhat softer in tone. It still possesses its original leather hammer coverings, which is a considerable advantage in terms of authenticity of sound, as Linda Nicholson explains. Today leather is tanned differently and therefore has a different texture to 200 years ago. Caspar Katholnick built a beautifully decorated piano in circa 1805, whose compass by now extends to five octaves and four notes. An instrument is displayed by Johann Fritz, likewise made in Vienna, politically quite incorrect as its legs are in the form of Moors who hold the body of the instrument on their shoulders– and have their hands over their ears... The fortepiano dates from between 1812 and 1815, and Linda Nicholson tells how it was discovered in a palace in Cremona , where it had hardly ever been played and so was in excellent original condition. The most incredible fact is that there are still the original leather coverings which were used to protect the legs when the instrument was transported. "We almost didn't find the legs because they were still wrapped in their leather coverings". There is a Conrad Graf of six and a half octaves from some 15 years later, (1828), that has one unusual feature: a second soundboard that sits above the strings in order to blend the sound better. A second piano by Graf (1831) originally had the same feature, but it is now lost. It also has a compass of six and a half octaves and represents the furthest development of the piano before metal frames were introduced. However this piano already has some openings in the bottom so that the sound can also emerge from below. |